The yield return statement is probably one of the most unknown features of C#. In this post I want to explain what it does and what its applications are.

Even if most developers have heard of yield return it’s often misunderstood. Let’s start with an easy example:

IEnumerable

While the above has no value for anything serious, it’s a good example to debug to see how the yield return statement works. Let’s call this method:

foreach(var number in GetNumbers()) Console.WriteLine(number);

When you debug this (using F11, Step Into), you will see how the current line of execution jumps between the foreach-loop and the yield return statements. What happens here is that each iteration of the foreach loop calls the iterator method until it reaches the yield return statement. Here the value is returned to the caller and the location in the iterator function is saved. Execution is restarted from that location the next time that the iterator function is called. This continues until there are no more yield returns.

A first use case of the yield statement is the fact that we don’t have to create an intermediate list to hold our variables, such as in the example above. There are a few more implications though.

Yield return versus traditional loops

Let’s have a look at a different example. We’ll start with a traditional loop which returns a list:

IEnumerable<int> GenerateWithoutYield()

{

var i = 0;

var list = new List<int>();

while (i<5)

list.Add(++i);

return list;

}

foreach(var number in GenerateWithoutYield())

Console.WriteLine(number);

These are the steps that are executed:

- GenerateWithoutYield is called.

- The entire method gets executed and the list is constructed.

- The foreach-construct loops over all the values in the list.

- The net result is that we get numbers 1 to 5 printed in the console.

Now, let’s look at an example with the yield return statement:

IEnumerable<int> GenerateWithYield()

{

var i = 0;

while (i<5)

yield return ++i;

}

foreach(var number in GenerateWithYield())

Console.WriteLine(number);

At first sight, we might think that this is a function which returns a list of 5 numbers. However, because of the yield-statement, this is actually something completely different. This method doesn’t in fact return a list at all. What it does is it creates a state-machine with a promise to return 5 numbers. That’s a whole different thing than a list of 5 numbers. While often the result is the same, there are certain subtleties you need to be aware of.

This is what happens when we execute this code:

- GenerateWithYield is called.

- This returns an IEnumerable

. Remember that it’s not returning a list, but a promise to return a sequence of numbers when asked for it (more concretely, it exposes an iterator to allow us to act on that promise). - Each iteration of the foreach loop calls the iterator method. When the yield return statement is reached the value is returned, and the current location in code is retained. Execution is restarted from that location the next time that the iterator function is called.

- The end result is that you get the numbers 1 to 5 printed in the console.

Example: infinite loops

Now you might think that since both example behave exactly the same, that there’s no difference in which one we use. Let’s modify the example a bit to show where the differences lie. I’m going to make two small changes:

- Instead of looping in the generator until we reach 5, I’m going to loop endlessly:

IEnumerable<int> GenerateWithYield()

{

var i = 0;

while (true)

yield return ++i;

}

IEnumerable<int> GenerateWithoutYield()

{

var i = 0;

var list = new List<int>();

while (true)

list.Add(++i);

return list;

}

- Instead of iterating directly over the list, I’m going to take 5 items of the list:

foreach(var number in GenerateWithoutYield().Take(5))

Console.WriteLine(number);

foreach(var number in GenerateWithYield().Take(5))

Console.WriteLine(number);

When we do this, the difference is clear. Following the previously described steps, in the case of the method without yield, the loop will never finish as it will keep looping forever inside the GenerateWithoutYield-method when it’s called in the first step (until it throws an OutOfMemoryException). In the case of the GenerateWithYield-method however, we get a different behavior. Because the Take-method is actually implemented with a yield return operator as well, this will succeed. The method only gets called until the Take-method is satisfied.

Example: multiple iterations

Another side effect of the yield return statement is that multiple invocations will result in multiple iterations. Let’s have a look at an example:

IEnumerable<Invoice> GetInvoices()

{

for(var i = 1;i<11;i++)

yield return new Invoice {Amount = i * 10};

}

void DoubleAmounts(IEnumerable<Invoice> invoices)

{

foreach(var invoice in invoices)

invoice.Amount = invoice.Amount * 2;

}

var invoices = GetInvoices();

DoubleAmounts(invoices);

Console.WriteLine(invoices.First().Amount);

Read through the above code sample and try to predict what will be written to the console.

What do you think the output is here? 20? In fact, the result is 10. Let’s see why:

- When the line var invoices = GetInvoices(); is executed we’re not getting a list of invoices, we’re getting a state-machine that can create invoices.

- That state machine is then passed to the DoubleAmounts-method.

- Inside the DoubleAmounts-method we use the state-machine to generate the invoices and we double the amount of each of those invoices.

- All the invoices that were created are discarded though, as there are no references to them.

- When we return to the main method, we still have a reference to the state-machine. By calling the First-method we again ask it to generate invoices (only one in this case). The state-machine again creates an invoice. This is a new invoice and as a result, the amount will be 10.

Because this is non-obvious behavior, tools such as Resharper will warn you about multiple iterations.

Real life usage

It’s pretty neat that we can write seemingly infinite loops and get away with it, but what can we use it for in real life? In broad terms, I’ve found two main use cases (all other use cases I found are a subclass of these two).

Custom iteration

Let’s say we have a list of numbers. We now want to display all the numbers larger than a specific number. In a traditional implementation that might look like this:

IEnumerable<int> GetNumbersGreaterThan3(List<int> numbers)

{

var theNumbers = new List<int>();

foreach(var nr in numbers)

{

if(nr > 3)

theNumbers.Add(nr);

}

return theNumbers;

}

foreach(var nr in GetNumbersGreaterThan3(new List<int> {1,2,3,4,5})

Console.WriteLine(nr);

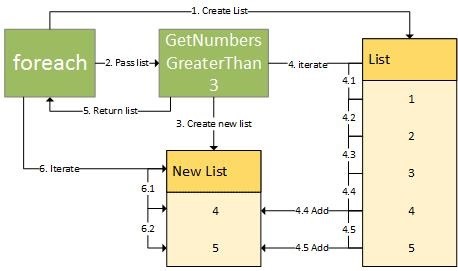

While this will work, it has a disadvantage: we had to create an intermediate list to hold the items. The flow can be visualized as follows:

You can see in the above image, how the first list is created, then iterated and filtered into a new list. This new list is then iterated again.

We can avoid this intermediate list by using yield return:

IEnumerable<int> GetNumbersGreaterThan3(List<int> numbers)

{

foreach(var nr in numbers)

{

if(nr > 3)

yield return nr;

}

}

foreach(var nr in GetNumbersGreaterThan3(new List<int> {1,2,3,4,5})

Console.WriteLine(nr);

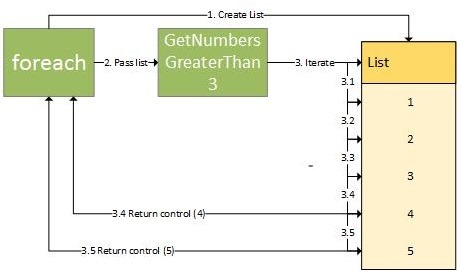

Now, the execution looks very different:

In this diagram it’s clear that we only iterate the list once. When we get to the items that are needed, control is ceded to the caller (the foreach-loop in this case)

Stateful iteration

Since the method containing the yield return statement will be paused and resumed where the yield-statement takes place, it still maintains its state. Let’s take a look at the following example:

IEnumerable<int> Totals(List<int> numbers)

{

var total = 0;

foreach(var number in numbers)

{

total += number;

yield return total;

}

}

foreach(var total in Totals(new List<int> {1,2,3,4,5})

Console.WriteLine(total);

The above code will output the values 1,3,6,10,15. Because of the pause/resume behavior, the variable total will hold its value between iterations. This can be handy to do stateful calculations.

Deferred execution

All of the above samples have one thing in common: they only get executed as and when necessary. It’s the mechanism of pause/resume in the methods that makes this possible. By using deferred execution we can make some methods simpler, some faster and some even possible where they were impossible before (remember the infinite number generator).

The entire LINQ part of C# is built around deferred execution. Let’s see a few sample how deferred execution can make things more efficient:

var dollarPrices = FetchProducts().Take(10)

.Select(p => p.CalculatePrice())

.OrderBy(price => price)

.Take(5)

.Select(price => ConvertTo$(price));

Suppose we have 1000 products. If the above method did not have deferred execution, it would mean we would:

- Fetch all 1000 products

- Calculate the price of all 1000 products

- Order 1000 prices

- Convert all the prices to dollars

- Take the top 5 of those prices

Because of deferred execution however, this can be reduced to:

- Fetch 10 products

- Calculate the price of 10 products

- Order 10 prices

- Convert 5 of these prices to dollars

While maybe a contrived example, it shows clearly how deferred execution can greatly increase efficiency.

Side note: I want to make clear that deferred execution in itself does not make your code faster. Inherently, it has no effect on the speed or efficiency of your code. The value of deferred execution is that it allows you to optimize your code in a clean, readable and maintainable way. This is an important distinction.

Conclusion

The yield-keyword is often misunderstood. Its behavior can seem a bit strange at first sight. However, it’s often the key to creating efficient code that is maintainable at the same time. Its main use cases are custom and stateful iteration which allow you to create simple yet powerful code. The yield-keyword is what’s powering the deferred execution used in LINQ and allows us to use it in our code. I hope this article helped explaining the semantics of the yield-keyword and the effects and implications it has on calling code. Feel free to ask any questions in the comments!